Key insights from our Cyber Byte: Crisis Communications Webinar

At the end of last year, we hosted a Cyber Byte webinar focused on cyber attack crisis communications, exploring how organisations can prepare for, respond…

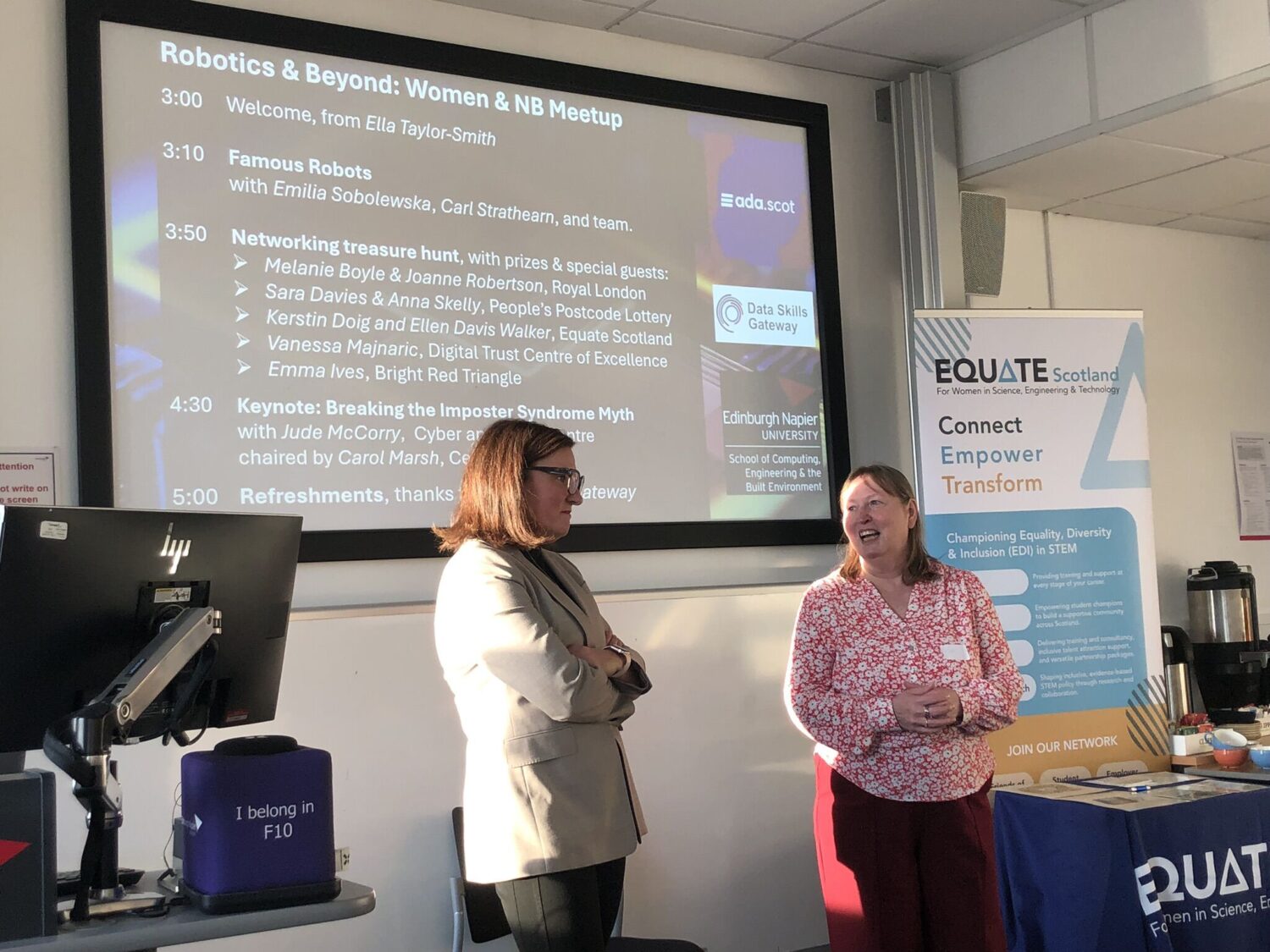

Last week, our CEO Jude McCorry delivered a talk at Edinburgh Napier University in celebration of Ada Lovelace Day; a day dedicated to recognising the achievements of women in STEM and inspiring the next generation of innovators.

In her talk, Jude spoke about the concept of impostor syndrome, something many people experience throughout their careers; especially women working in tech and leadership roles. Drawing from her own experiences and research, she explored where these feelings come from, why the term itself might be misleading, and how we can all begin to challenge it.

Below, Jude shares her reflections in full.

Rethinking Impostor Syndrome

I used to think “Impostor Syndrome” was a trendy term that had only emerged in recent years as something everyone suddenly jumped on. But after digging into its history and psychology, I realised it’s been around for decades.

In the tech world, I’ve heard countless women say they struggle with impostor syndrome. They feel inferior to their male colleagues, isolated as the minority, or like they simply don’t belong in the room. That made me want to understand it more deeply.

Where It All Began

Back in the 1970s, two American psychologists, Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes, were also puzzled by this phenomenon. In 1978, they published a paper introducing the concept of impostor syndrome. They had interviewed 150 high-achieving women who, despite clear evidence of their abilities, consistently downplayed their accomplishments. Many attributed their success to luck or to others overestimating them.

The term “impostor syndrome” quickly took hold. Like ABBA, punk rock, and The Bay City Rollers, the phrase became part of the cultural fabric of the time. It resonated because it offered a simple explanation for the anxiety and self-doubt we often feel when facing difficult tasks. Clance and Imes described it as a pattern of doubting one’s accomplishments and fearing exposure as a fraud.

The Psychology Behind It

Impostor syndrome follows a specific psychological process. It often begins when you’re given a task you don’t feel ready for. Anxiety, self-doubt, and worry creep in. You might respond by obsessively over-preparing; or by procrastinating and avoiding the task altogether (like me writing this blog!).

Once the task is done, you feel relief and maybe even a fleeting sense of accomplishment. But soon after, you start picking it apart. If you are over-prepared, you credit the success to hard work, not ability. If you procrastinated and still succeeded, you chalk it up to luck or winging it.

Either way, the result is the same: any positive outcome reinforces the belief that you’re a fraud, and the fear of being found out grows. It’s a vicious cycle.

Why the Term Itself Is Misleading

The phrase “impostor syndrome” is, in my view, flawed. An impostor is someone who deliberately deceives others. But people with impostor syndrome aren’t pretending, they’re often being reassured by others that they’re capable, while internally struggling to believe it.

And “syndrome” implies a medical condition. Impostor syndrome isn’t a disease, psychological or otherwise. It’s a common, human experience.

What Can You Do About It?

Edit Your Story

If you’re prone to impostor feelings, reframe your narrative. Most people find difficult situations challenging, it’s normal. Feeling like an impostor from time to time doesn’t mean you are one. With practice and persistence, it gets easier. Remind yourself that starting something new is always hard at first, but it gets better.

We See the World from the Inside Out

People are often surprised when I say I get nervous before TV interviews or public events. But here’s the thing: we see ourselves from the inside, aware of every flaw, doubt, and insecurity. We see others only from the outside, this is the confident face they present to the world.

So next time you feel like you don’t belong, remember you’re only aware of your own inner world, not theirs. They might be just as nervous as you.

Feelings ≠ Facts

Albert Einstein once said to a friend:

“The exaggerated esteem in which my life work is held makes me very ill at ease. I feel compelled to think of myself as an involuntary swindler.”

If Einstein felt like an impostor, you’re in good company. Just because you feel like a fraud doesn’t mean you are one. When those feelings arise, pause and look at the evidence:

Apply for that job you’re 70% ready for, you’ll learn the other 30%. Look at your kids and think, “I’ve kept them healthy and happy (even if I once force-fed them carrot soup-sorry, teenager!).” Reflect on your journey. Look at old photos. See how far you’ve come.

Aim to Be Good Enough, Not Perfect

Perfectionism feeds impostor syndrome. When I had my first child 19 years ago, I thought everything had to be perfect; the house, the routine, the meals. A few weeks in, my dad said, “There’s nothing wrong with staying in your PJs all day and ordering a chippy for tea.” It was his way of saying: loosen up.

He was right.

Donald Winnicott, a psychoanalyst and paediatrician in 1950s London, found that mothers striving to be perfect were more likely to become depressed. Those who aimed to be “good enough” were healthier and happier. Perfection is unattainable. Chasing it leads to disappointment.

Winnicott’s advice? Do your best with the gifts you have. Be good enough. That’s more than enough.

So, ladies, less of the “impostor syndrome” chat. Remember, you are good enough, more than good enough, and you more than belong. You’ve got this.

Jude McCorry

CEO, Cyber and Fraud Centre – Scotland